DRMacIver's Notebook

How can we create healthy geniuses?

How can we create healthy geniuses?

Here’s another abandoned draft. I think this one was intended for the paid subscriber archives. It’s clearly related to How do we treat unique talents?, although I don’t remember which one came first.

A recurring talking point in parts of where I hang out on Twitter is something along the lines of “hypercompetence is a sign of trauma, healthy individuals aren’t hypercompetent”. This seems to me to be broadly true, but I think it’s true for nonobvious reasons that I’d like to explore.

What is Hypercompetence?

Hypercompetence is some truly unusual degree of expertise in some specific skill. People are not, generally, hypercompetent in some fully general sense, they are hypercompetent at something in particular. This might be a professional skill (mathematics, writing, golf, etc), a hobby, a social skill, or something else entirely.

I think it is worth distinguishing hypercompetence from normal expertise. Expertise is normal - you just have to work hard at getting good at a thing, and eventually you will be. In the sense of Difficult Problems and Hard Work, for most people and skills, acquiring expertise in that skill is just hard work rather than a difficult problem. The hypercompetent individual however is somehow on a whole other level.

The distinguishing feature of hypercompetence is not that it is competence but that it is hyper. You look at them compared to their peers, and there is a major qualitative difference between them that seemingly cannot be explained by normal skill development. I’m imagining here someone like Paul Erdős, who was just the most ridiculously prolific mathematician.

(Also a good example of “healthy people aren’t hypercompetent”. If the price for being as good as Paul Erdős was that you had to be Paul Erdős, I cannot imagine many people would take that deal.)

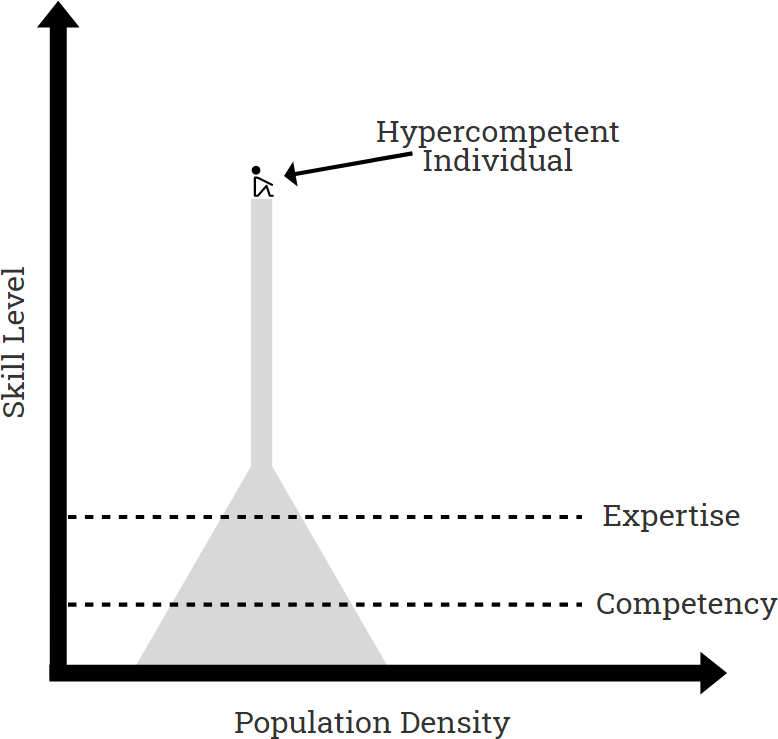

Here is a diagram. It may not make much sense because I am bad at drawing diagrams, but I find it helpful.

In this diagram imagine each vertical line is a person at their skill level, so the width of the shaded area is proportionate to the number of people at that skill level (not realyl to scale - the spike in the middle is meant to be a single person, but I broadened it for clarity). So you’ve got a normal level of expertise that gradually tapers off as you go up, and then you’ve got the hypercompetent individual who is out there on their own, as much above the normal experts as the normal experts are above the average member of the population.

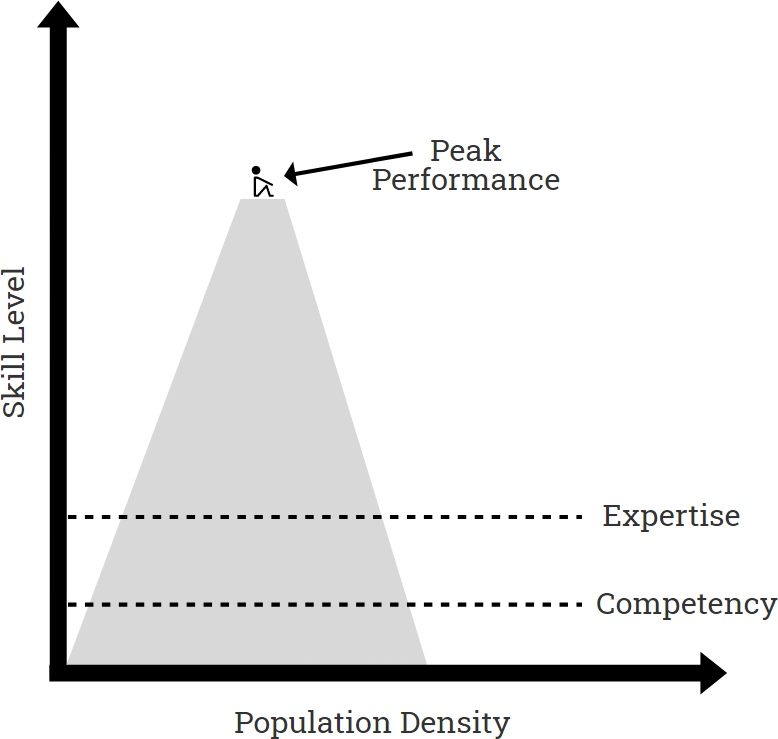

In contrast, the following person is exactly as competent as the hypercompetent individual in our above example, but the skill level smoothly climbs towards their level:

They are no less skilled than the hypercompetent individual, and they are still the most competent individual in the population, but the key difference is that they are surrounded by people who are only slightly less competent than they are. There is a clear path to where they are, with every step along the way populated.

I am fairly into the goal of helping everyone be the best versions of themselves, so I much prefer the latter scenario. In the former, there a sharp cliff where people have no real idea how to improve past other than this one outlier who we don’t know how to replicate. This seems like a missed opportunity, and I would like to figure out how we can use instances of the former to produce the latter.

Social Superpowers

At least some hypercompetence, especially with social skills, is learned in response to suffering. The Ferret argues that “superpowers” are compensation for old trauma - if you’re, for example, super attuned to other people’s emotional states, it might be because you grew up in an environment where you needed to be hyperaware of people’s emotional states to stay safe.

This seems obviously bad (although the competencies arrived at this way are often good). It can be worth treating the superpower as somewhat diagnostic of things to look at, but the superpower doesn’t just go away because you fix the underlying issue, you’ve still learned how to do it. e.g. I’m very good at explaining things, this turns out to be partly due to a somewhat inaccurate belief that if people are being mean to me and I just explain myself really well they’ll understand and stop being mean to me. This works about as well as it sounds, but it appears to have prompted some useful skill development.

Social superpowers are hard to learn because we’re incredibly bad at teaching social skills, to the point of not even trying. I suspect this is a scenario where the solution to the problem starts with trying literally anything at all.

Why is genius bad so often?

I’m more interested in the sort of hypercompetence that might reasonably be called “genius”, which I think tends to arise out of some amount of baseline ability, adequate resources to make use of it, and some sort of overriding obsession.

(Of the three, I most clearly lack the obsession. I have a bit of an internal debate as to whether this is missing the boat or dodging a bullet, but I think for some of the reasons I discuss here my life is the better for it. Which is not to say that I think I’d be a genius if I could be sufficiently obsessed, but I think I’m at least in with a chance)

Being vastly better at something you care about than people around you who also care about that thing is very unpleasant. It triggers many of the norms I described in The social obligation to be bad at things, and it is the very definition of a nice problem to have, isolating you from those around you who think they would love to have your problems.

This is bad because being socially censured and/or isolated is bad for people. It’s also bad because it means they don’t have peers they can readily discuss their problems with to get a different perspective on it - the run-of-the-mill experts can to some degree serve these functions, but they can’t really relate to the hypercompetent individual that well, and in many ways are probably more resentful of them than your average run of the mill citizen who didn’t care that much about being good at the thing in the first place.

The other reason why it is bad is that it indicates that the hypercompetent individual is someone who chose to do it anyway, and that’s probably not a sign of a healthy person.

A useful heuristic is that, to the best of their abilities and resources, people get the life they optimise for. A genius “could” have chosen to just go hang out on the beach and drink margaritas, but that is not the life they chose. Instead, they chose a life which deliberately isolates them, because they have decided that they care far more about their particular level of competency than they do connection with other people.

More than this, they are so far past the typical level of those around them that what happened is that they got to the point of social censure, looked around them, and kept going because it was that important to them.

I can, perhaps, imagine a healthy person rationally choosing to do that given sufficient positive motivations to do this. If that’s you, no judgement. But for most people I don’t think that’s what’s happening: Instead they struggle to connect with others, and as a result they end up (either deliberately or emotionally) concluding that they can’t, and so they set it aside.

I think what often happens here is something akin to the protective mechanism I described in Burnout as Acedia. People learn that caring about social connection is not rewarded, and may be punished, so they learn “not to” care about it.

Postscript

I don’t know why this particular piece got abandoned. It’s been sitting in the drafts folder for too long. I suspect it’s simply that I don’t know how to answer the question, and so didn’t know how to wrap it up.