DRMacIver's Notebook

Rules as moral training wheels

Rules as moral training wheels

Here’s the final draft bankruptcy piece. It’s a pity, because I think it’s a good piece, but it turns out that I absolutely do not want to write about ethics right now.

It’s definitely not going to hold together as a cohesive whole, sorry, this is in a stage where I was pulling a bunch of disparate pieces together and haven’t yet done the work to join the dots. Hopefully the individual bits will be interesting though.

Good people don’t need rules

One response I got to learning to walk through walls was surprise that I didn’t talk about ethics in it. Many things become easier when you let go of your ethical rules, right?

I think it’s a mistake to think of it this way, and ethics should be treated not as part of the rules you operate under, but instead about the goals you are trying to achieve. Being a good person isn’t about only doing good things, it’s about wanting to do good things and not wanting to do bad things.

One place this comes up is in the strawman version of a common argument between religious people and atheists, where the religious person asks what stops you going around murdering people without god, and the atheist’s response is that the thing that stops you from murdering people is not wanting to murder people.

I’m not suggesting that this is a fair and accurate summary of the argument. The strawman version of it is usefully illustrative in the same way that our opening anxiety loop parody was.

Ideally, ethics shouldn’t be about a set of rules that must be obeyed, but instead baked into your motivations and view of the world. This is hopefully fairly intuitive. Would you really e.g. think well of your someone if you knew that they really wanted to go out and do some murder and the only thing stopping them was their sense of ethics?

Rules as a necessary developmental stage

Of course, in order to get to this ideal state, you sometimes have to pass through non-ideal ones.

There’s a great section from an interview with Robert Kegan (a famous developmental psychologist) I watched a while ago. Here’s a cleaned up transcript of it:

I was talking with a social worker the other day who works with adolescents who have come out of the court system and who’ve committed crimes.

She was talking about a young man maybe 16, 17, years old who had a record of auto theft, and she told me about a session she had with him where he he came to her and said “you know you’d be proud of me because, I know I shouldn’t, but I do still hang out with a number of rough friends who could easily get me in trouble, and just this weekend I was hanging out with them and they wanted they wanted me to join them in stealing a car, and ordinarily I might have just gone along with that, and because of our work together I didn’t.”

And she said “I’m really glad to hear about that. Tell me a little bit more.”

He said “well they wanted me to steal this car and I was going to and I stopped and I thought to myself that if I steal this car there’s a very good chance we’re gonna get caught, and if I get caught, because I’m on probation, unlike these other friends, they’re gonna get let off but I’m gonna go back to jail.”

She said to him “well, I’m really glad that you didn’t steal the car, but I have to be honest and say that I wished the reason you chosen not to steal the car was not just that if you did you might go to jail, but because you gave some thought to how that person would feel and the fact that his car’s not your car and then he would naturally feel bad.”

And she said he just looked right at her and he said “yes, but I’m not there yet”, and she she sat back and she thought that was a beautiful answer that he was being absolutely truthful and that her hope for him was a little further ahead of where he was.

She was kind of telling a story on herself kind of saying how you know you can learn from your clients, even from your 16 year old clients.

Because it’s Robert Kegan, he naturally (and probably at least partly correctly) interprets this as a developmental psychology stage transition:

When he said “I’m not quite there yet”, from a developmentalist point of view we would also feel like he was telling a very important truth.

What he was saying was “just give me credit for the fact I didn’t steal the car, but my underlying logic is still about what’s in my best interest and the reason I didn’t steal it was because I had at least enough foresight to consider that I could get caught, I could get sent to jail”.

That is itself a given stage of development. It is the stage that comes before the socialized mind. What she was hoping for was a qualitatively different stage where people live not only to pursue their own interests and look at others as sort of opportunities to get their own needs met, or obstacles to getting their needs met, but where you actually begin to internalize something of the the values and beliefs of others around you. It starts with your society, as that make it conveyed through your immediate family, or your faith community or others beyond it, and eventually there’s the possibility that I start relating to others - family members, friends, society not just in terms of getting my own needs met but where I actually become more a part of society, because society has become more a part of me.

I begin to internalize the values, beliefs, and expectations of important people around me.

We call that the socialized mind, because you begin to develop the internal psychology that permits socialization, that permits you to become a member of a tribe that permits you to become a part of a community of interest larger than one, larger than your own self-interest where you will be able to actually subordinate some of your maybe short-term interests on behalf of enhancing the relationship, and when that stage evolves, typically in adolescence, it is a cause for relief and celebration on the part of parents and the community at large who live with this adolescent.

It enables employers of fast-food businesses who want to hire teenagers to feel they can hire a person who’s begun to make that transition because they become trustworthy you can kind of count on them they may be able to keep their agreements not just because they’ll get into they don’t but because they want you to continue to trust them and to respect them.

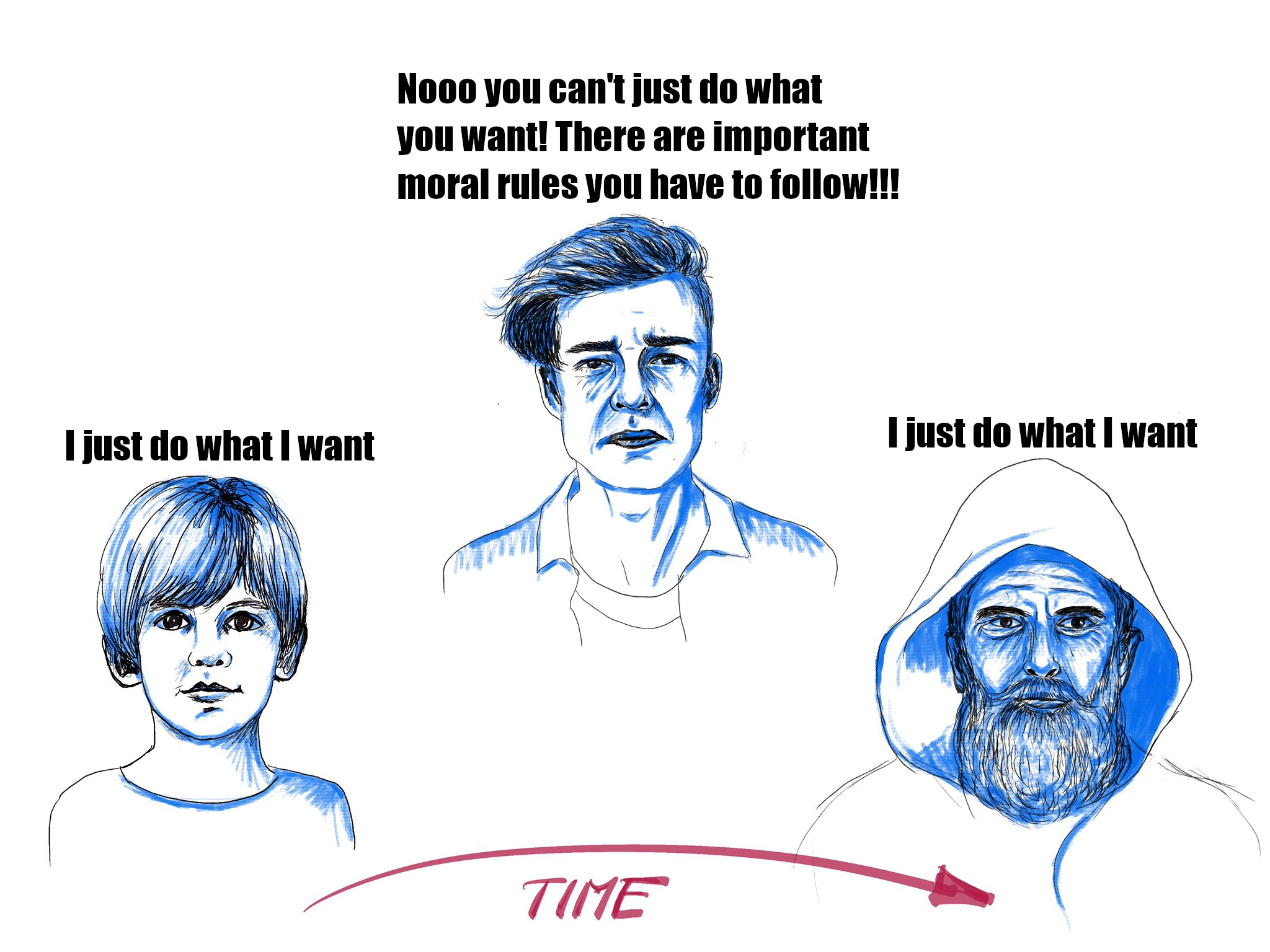

(Credit to Made in Cosmos for the original teenager meme)

In order to get to the point where your ethics is properly integrated into your motivations, you probably need to pass through a period where you hold very tightly to ethical rules. This is a good learning tool, but holding onto it too tightly or for too long is bad for you.

Think of it like training wheels: They’re very useful when learning to ride a bike, but if you never take them off you’ll never actually become a proficient bike rider.

The non-composability of ethical rules

The big problem with rules is that they conflict, and then what do you do?

The big central rule based ethical philosophy is called deontology, and is often associated with Immanuel Kant. In deontology there are inviolable rules that you are supposed to follow in order to be ethical.

Where those rules come from varies. I think the most common place to find real deontologists in the wild is in religion, which has the nice simple answer that rules come from god. I think, in practice, even religious people tend not to be pure deontologists, but there is a strong deontological component to their beliefs.

Kant instead believes that rules are derived from the “categorical imperative”, a term that definitely doesn’t mean “whatever Kant made up based on his prejudices as a 18th century middle class Austrian philosopher”, but instead is about acting in accordance with universalizable principles. e.g. you shouldn’t lie because a world in which everyone lied freely wouldn’t function.

The problem with having hard and fast ethical rules is that sometimes they will contradict each other. For example, suppose you’re in Nazi Germany and, as a good person, are hiding a Jewish family in your attic. A Gestapo officer comes to your door and asks if you’ve seen any Jews around. You know full well that the fate in store for them if caught is a concentration camp. Do you lie to the Gestapo?

Kant thinks you should tell the Gestapo the truth.

Kant is wrong.

There are many points of ethics on which I think reasonable people can disagree, but this is not one of them. Anyone who claims the correct thing to do is to tell the truth to the Gestapo agent is a bad person (or at least claiming ot be one) and is not to be trusted.

The problem here is that we have two conflicting duties: To protect the lives of the family sheltering with us, and to tell the truth. We are not able to follow both (Or, at least, the path to following both is not obvious to us in the moment - possibly a sufficiently clever person could come up with a workaround, or possibly you could apply your mad Jiu Jitsu skills and punch out the Nazi, or possibly a time traveller from the future could… The point is that we work with the resources available to us in the moment), and thus must choose between them, and much of the time even if there is theoretically a path available that resolves the contradictions, in the moment we must navigate the fact that we see no such path. This isn’t solvable by pre-gaming every ethical conundrum we find ourselves in, because the world is complex enough that we cannot anticipate everything), and this leads us to ask the question we probably should have asked at the start: What do we mean by should? What actually happens if we break one of these ethical rules?

(It’s unclear to me whether Kant thinks this is an example of a contradiction in rules (mostly because I haven’t checked too hard because the more I read Kant on ethics the more I want to not read Kant on ethics and also the more I wish I had a time machine so I could go back in time and slap Kant), but to me it is reasonably clear that at least one of two things are true: a) There is a moral duty to protect the Jewish family in this example or b) Duties to follow rules are not sufficient to describe the ethical requirements on being a good person, and those duties must sometimes be overruled.)

Here’s part of an answer: You should feel guilty about it, regardless of whether it was the correct thing to do.

The feeling of guilt

So you did something slightly wrong. Honestly, you knew it was wrong, why did you do it? Only a monster deliberately does wrong things. Therefore you’re a monster. You know it. You’re the worst.

But wait! Maybe you were forced into it! Or maybe you in fact had a very good reason for doing the thing. Maybe it’s completely justified and not wrong at all, and therefore you don’t have to feel guilty and are not a monster after all! Yes, this must be the case, you’ve done nothing wrong and you will continue to argue that you’ve done nothing wrong until the part of you insisting that you have stops trying to make you feel guilty.

In fact, it’s the people who forced you into this situation who are at fault. They’re the real monsters. You should punish them.

This is, of course, a huge exaggeration of the thought process most people go through, but it’s not as much of an exaggeration for everyone as you might hope, and many of us go through some smaller version of it on a pretty regular basis.

Let’s talk a bit about what’s going on here.

For many people, guilt is one of the worst emotions they regularly experience.

Footnotes

This essay had some huge footnotes, and they don’t really make sense integrated into the main text, so here they are as a subsection.

The Doctor on virtue

In one of those oddly memorable scenes from otherwise forgettable media, here’s The Doctor on the subject of good mean not needing rules:

Madame Kovarian: The anger of a good man is not a problem. Good men have too many rules.

The Doctor: Good men don’t need rules. Today is not the day to find out why I have so many.

Kant on lying to murderers

Naturally Kant didn’t use the Gestapo example because it was a bit after his time. In his original conception it’s a murderer. The Gestapo example seems to have become widely used though.

I was worried that I was being unfair to Kant and that his actual opinion is likely to be more nuanced, so I looked up the original.

So, here is his argument, from “On a supposed right to tell lies from benevolent motives”:

For instance, if you have by a lie hindered a man who is even now planning a murder, you are legally responsible for all the consequences. But if you have strictly adhered to the truth, public justice can find no fault with you, be the unforeseen consequence what it may. It is possible that whilst you have honestly answered Yes to the murderer’s question, whether his intended victim is in the house, the latter may have gone out unobserved, and so not have come in the way of the murderer, and the deed therefore have not been done; whereas, if you lied and said he was not in the house, and he had really gone out (though unknown to you), so that the murderer met him as he went, and executed his purpose on him, then you might with justice be accused as the cause of his death. For, if you had spoken the truth as well as you knew it, perhaps the murder while seeking for his enemy in the house might have been caught by neighbours coming up and the deed been prevented. Whoever then tells a lie however good his intentions may be, must answer for the consequences of it, even before the civil tribunal, and must pay the penalty for them, however unforeseen they may have been; because truthfulness is a duty that must be regarded as the basis of all duties founded on contract, the laws of which would be rendered uncertain and useless if the least exception to them were admitted.

To be truthful (honest) in all declarations is therefore a sacred unconditional command of reason, and not to be limited by any expediency.

This is, to be blunt, a really fascinating combination of blatant motivated reasoning and sheer moral cowardice. Kant’s argument is that you should do the action you know is likely to get people killed because then you will not be blamed for any negative consequences?

On the subject of blaming Kant for negative consequences of his actions, when I complained about this passage on Twitter, Matt Bateman sent me the paper “Maria von Herbert’s Challenge to Kant” which is an exchange he had with a devout Kantian, who was looking for moral guidance about a situation in which she had told the truth (to a new lover, about the fact that he was not her first) after concealing it initially. She is distraught, and seeking not so much abstract reasoning as guidance:

Herbert writes that she has lost her love, that her heart is shattered, that there is nothing left to make life worth living, and that Kant’s moral philosophy hasn’t helped a bit. Kant’s reply is to suggest that the love is deservedly lost, that misery is an appropriate response to one’s own moral failure, and that the really interesting moral question here is the one that hinges on a subtle but necessary scope distinction: the distinction between telling a lie and failing to tell the truth, between saying ‘not-p’, and not saying ‘p’. Conspicuously absent is an acknowledgement of Herbert’s more than theoretical interest in the question: is suicide compatible with the moral law?

After several letters in exchange she does, in fact, commit suicide. While I don’t think it’s entirely fair to blame Kant for this outcome, I think his behaviour throughout definitely doesn’t suggest he has any practical insight into how to be a good person.

Postscript

The reason this draft got abandoned is pretty clear to me right now because I was literally in the process of writing it when I abandoned it: I just don’t want to write about ethics right now. I’m tired and grumpy and depressed, and this whole subject makes that worse rather than better, because I don’t have the energy for a proper righteous anger which is the actual useful emotion that can drive me to write about ethics. I’m going to go find something more fun to write about.