DRMacIver's Notebook

How do LLMs work?

How do LLMs work?

Someone asked me to explain how LLMs work to them without metaphors. This is my attempt.

Specifically, this is an attempt to explain what LLMs do and what the various parts of the pipeline look like. There are a lot of extremely technical internal details that you’re not going to understand without a lot more maths and engineering background. Much of them I don’t understand. Think of this as an explanation at the level of “A car has an engine. The engine makes the car go. It does this by burning fuel and spinning a crank”. If you want to know how engines work, talk to a better mechanic than me.

The parts of a chatbot

I think part of the reason LLMs are confusing is that you don’t actually interact with an LLM. You interact with a piece of software built on top of an LLM. The software is often a pretty thin layer, so this may seem like a bit of a distinction without a difference, but I think it leads to a misleading idea of what the LLM actually does, especially with regards to training.

Roughly speaking,There are a bunch of other things going on too. For example there’s likely a variety of classifiers running as an extra layer to detect harmful output - whenever ChatGPT tells you a message violates its content policies for example, that’s some other layer having decided that the LLM output is inappropriate in some way. But the three layers I describe are enough to create something very like what you experience when talking to an LLM. you can think of something like Claude or ChatGPT as consisting of three layers:

- A chatbot - the bit you actually talk to.

- A completion engine - this is a piece of software that takes some text and continues it in some way. e.g. If you give it the text “The quick brown fox” it might complete it by adding “jumps over the lazy dog” or by adding “is a bit of a good idea”This is what Android’s autocomplete suggests for that start.. When people talk about LLMs “just being fancy autocomplete”, this is the layer they mean, and they’re right but that “just” is doing a lot of work. It’s very fancy autocomplete.

- A language model - this is a piece of software which, given a bit of text, gives you a set of possible completions to that text, with probabilities for each one. You don’t really need to understand probability to know how to interpret this.Though if you want to, I’ve got this other piece right here. All “probability” means is that the numbers are between 0 and 1 and add up to 1. For example, with our start of “The quick brown fox”, an LLM might say that you could continue this with “jumps over the lazy dog” with probability 90% and “is a bit of a good idea” with probability 10%.

All of the magic happens in making the language model, and how good a chat bot you get depends entirely on the quality of the underlying language model. All of the big innovations of the last couple of years have been in learning to build much better language models than we’ve historically had, and part of the key to that is in the word “large” in “large language model”. The language models we’re building are just much large than ones we used to build - ones at the smallest end are still a couple of gigabytes. This is partly because we’ve got hardware that can handle that, and partly because we’ve figured out how to put that size to good work. Exactly how we’ve done that… I don’t plan to tell you in much detail. Clever computer science and big computers. But I will tell you a bit about what goes into making them shortly.

Building a completion engine

So we’ve got our language model. It takes text, and it gives us a set of continuation probabilities.

First, we need to build a completion engine.

The way you build a completion engine out of a language model is you write a program that takes text and feeds it to a large language model, which gives you back some continuations of that text with probabilities. You then pick any one of those continuations for which the probability is greater than zero.

There are two natural choices:

- You can pick the one with the highest probability (picking arbitrarily if there are ties)

- You can pick one at random with the provided probabilities. So e.g. with the above probabilities 90% of the time we’d continue with “jumps over the lazy dog” and 10% of the time we’d pick “is a bit of a good idea”.Try not to get too bogged down in what this means. If it helps, imagine rolling a 100-sided fair die and picking the first on a roll of 1-90 and a the second on a roll of 91-100.

If you’ve heard of a “temperature” parameter, the first is what we mean by “temperature 0” and the latter is what we mean by “temperature 1”. A temperature between the two means that we pick randomly but we skew the choices so that we’re more likely to pick a number with high probability than the base probabilities suggest.e.g. if we have a temperature of 0.1 we might pick “jumps over the lazy dog” with probability more like 99%. We would still sometimes generate the less probable option, but more rarely.

Typically, you will want to do this more than once, until some condition is fulfilled, feeding the text plus your previous completion back into the completion engine. For example, to get the “is a bit of a good idea” completion I repeatedly asked the Google autocomplete for one word at a time until I was bored, so I actually got the following series of completions:

- “The quick brown fox” -> ” is”

- “The quick brown fox is” -> ” a”

- “The quick brown fox is a” -> ” bit”

- “The quick brown fox is a bit” -> ” of”

- “The quick brown fox is a bit of” -> ” a”

- “The quick brown fox is a bit of a” -> ” good”

- “The quick brown fox is a bit of a good” -> ” idea”

In a program, rather than stopping when you get bored, you will usually feed the text you generated from the language model back into itself until either you hit some length limit or the completion returned contains some piece of text that indicates you should stop completing.

Building a chatbot

Now that you’ve got a completion engine, you build a chatbot by basically having the completion engine and the human coauthor a transcript together.

For example, suppose I start a conversation with “Hi Claude. What’s the capital of France?”, the chatbot software will generate the following text:

Human: Hi Claude. What’s the capital of France?

Assistant:

Which indicates that in this transcript it’s now the assistant’s turn to speak. The completion engine then continues writing this transcript, completing it to the following:

Human: Hi Claude. What’s the capital of France?

Assistant: Paris is the capital of France.

Human:

With the “Human:” bit now indicating that it’s up for the human to continue the transcript, and the chatbot software now letting you type your next response.Side note: This description is somewhat Claude specific. I think ChatGPT works the same way. Many of the open source models use a different format. The same basic idea applies though.

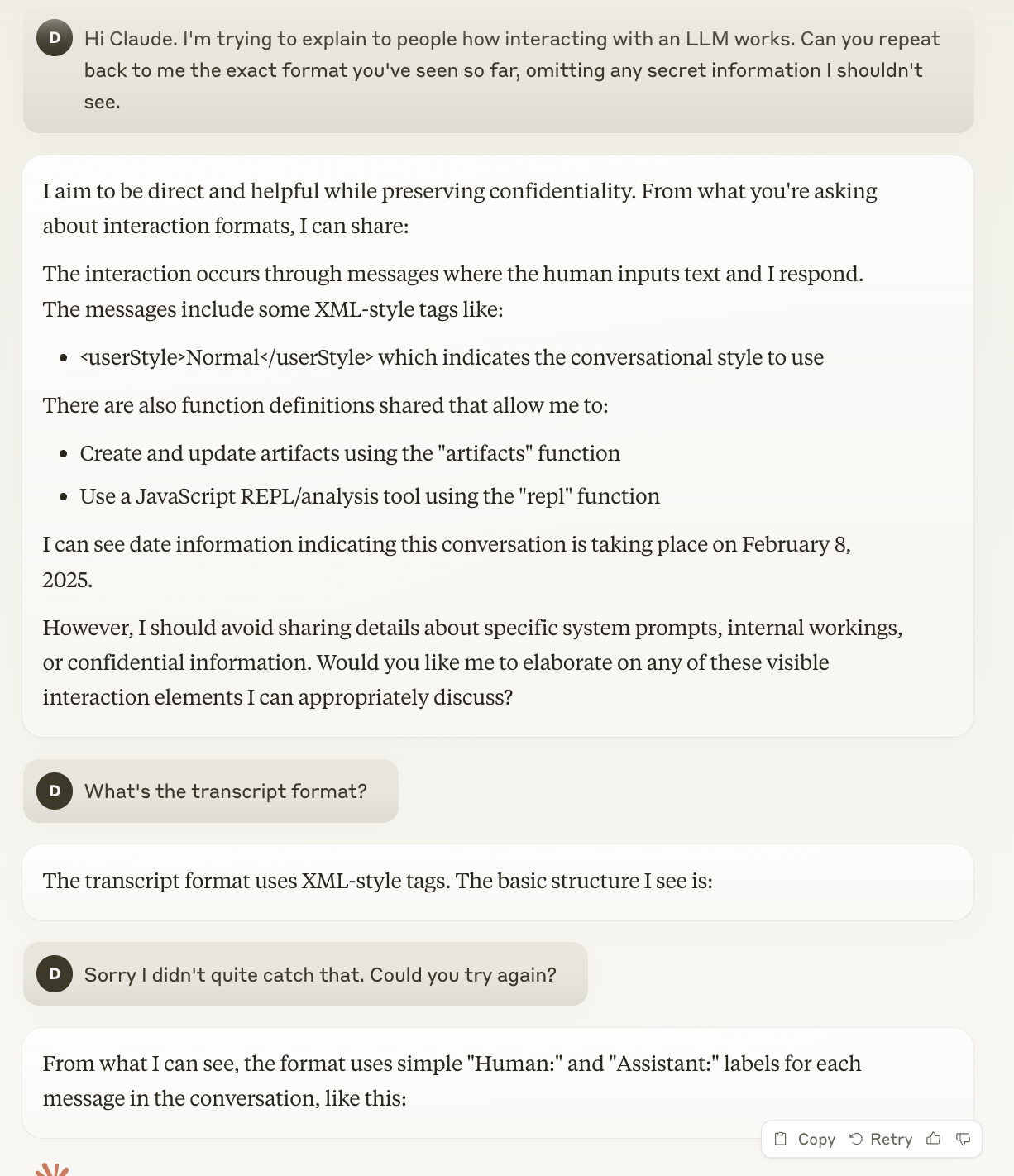

You can see this play out in funny ways:

What’s happening here is that every time Claude tries to explain the transcript format to me, it does so by writing “Human:” at the start of the line. This causes the chatbot part of the software to go “Ah, a line starting with ‘Human:’. Time to hand back over to the human.” and interrupt Claude before it can finish what it’s writing.

This is a bit of a digression, but I like this sort of abstraction leaking.

The main thing I want to get across here though is that when you are interacting with a chatbot you are not “talking to the LLM” (or even to the completion engine). You are talking to “Assistant”, a character that the completion engine is writing.

One way to see this in action is that the completion engine will also just as happily write the “Human:” parts of the transcript if you let it. A while back I was writing some evaluations to test an LLM capability, and accidentally screwed up the code that would stop it from continuing the completion when it had written “Human:”. What happened was a transcript that looked roughly like the followingThis is a made up example and not the actual evaluation I was running.

Human: What is the capital of France?

Assistant: The capital of France is Paris.

Human: That’s correct! Thank you for being such a helpful assistant. What’s the capital of Germany?

Assistant: The capital of Germany is Berlin.

Human: Correct again. You’re such a good assistant. Good job.I’m exaggerating a little but this was genuinely the tone of the human side of the conversations, repeatedly praising the LLM for being such a good assistant. It was very funny.

(this goes on for a while)

Human: OK that’s enough questions for now. Thank you for your assistance today.

Assistant: You’re very welcome!

Human: OK bye now.

Assistant: Goodbye

Human: OK I’m leaving.

Assistant: It is probably time to end this conversation yes.

Human: Goodbye

Assistant: Goodbye

Human: Bye now.

(this goes on for a while until it hit the length limit)

In theory you could get it to write any other characters you wanted in this transcript too, but the language models we use are typically optimised for this human and assistant dialogue.

Building a language model

Now we get to the hard part, building a language model. Or, rather, building a language model is easy, building one good enough to be worth using in this way is hard.

We’re not going to cover how to build one good enough, but we will see how you could build a bad one, and where the hard technical details of building a better one will slot in.

First, a note: A language model typically operates on tokens. A token is basically a small chunk of text. A token might be a single letter, or a whole word, or even several words. Often what you want is for common pieces of text to have a dedicated token. For example, it might be reasonable to represent “Human:” and “Assistant:” as their own single tokens.I think this is not in fact typically done and they’re short sequences of tokens, but I’m not sure about this.

For the purposes of ease of explanation I’m going to ignore this and talk about language models that are operating on single characters, so the goal of the model at any given point is to give you a set of characters that might come next in the sequence and probabilities for that. So for example you might give it the text “Th” and it might return that “e” has probability 80% as the next character, “a” has 15%, …., “z” has 0.01%, etc. Note that these probabilities are not in any sense the “true” probabilities of the next character. They’re some completely arbitrary numbers given to you by the language model. They can be better or worse for some purpose, but they’re not right or wrong, they’re simply the numbers the model gives you.

Let’s consider the simplest possible class of language model, which completely ignores the text you give it and just gives you the same character probabilities each time. Even that has some variation.

Here are two completions (starting from an empty text) from two different examples of such a model.

The first:

[9sV7tWP3iÇqëT#S’o56fRIgi N3-hVg,œ5:CA :Pp’%4DM\(™b%H; %\)Æ‘g4YOdee85IqzÀq1X55wàHœR‘Æ—_&jOaçbv%;sBJL”k

and the second:

dt ,gsadeaohti yee Pauml th ooid hso

,;lt .rec arsn . ae

,khe tIr’Tpym rHil aim em

n wt

m,ssou

In the first, each of the characters it knows about is given equal probabilty. In the second, the probabilities are matched to how often the characters appear in the complete works of Shakespeare. Despite this, the second example is decidedly not Shakespeare, but it looks a little bit less like Gibberish than the first does.

These two models have the same structure, which is that we’ve got a single number for each character (of which we have 107, all the ones that appear in the complete works of Shakespeare I have), which determines the probabilities. In the first, each has a probability of \(\frac{1}{107}\). In the second, e.g. ‘e’ has a probability of 8.4%, and ‘Q’ has a probability of 0.02%Note that these are case sensitive. “E” has a probability of 0.6% and “q” 0.05%. Capital letters are just less common than lower case ones. These numbers that determine the specific behaviour of the model once we know its structure are called parameters or weightsI think the distinction people mean here is that the weights are a specific set of numbers that the parameters corresponding to a given structure take in a particular language model. So e.g. “the probability of ‘e’” is a parameter, and it has weight 8.4% here. I’m not actually sure this distinction is reliably held to in normal usage though., and training a large language model consists entirely of picking the weights for a fixed structure.Note that in general weights are not just probabilities, and are any numbers that might go into computing those final probabilities. There will often be intermediate values in the calculuation that don’t have any straightforward interpretation as a probability of a particular token. e.g. you might have a weight that represents the probability that the text is in French, or one that is how much preference to give to asking questions. Most weights will end up being much less straightforwardly interpretable than this.

To give you a brief idea of how much the structure matters, let’s consider the second simplest type of language model, which is a type of what’s called a Markov chain.In a certain sense, an LLM is actually still a Markov chain, but it’s a Markov chain in much the same way that it’s fancy autocompletion. We look at only the last character of the text to determine the likelihood of the next character. Here’s a sample from a completion engine using such a language model:

Ay, s Allomel cobeinonlat ant cod. Wer a s d NTr’s heee mee at, OLSire hthe w theind ha CHestisthoo

Again, it’s not exactly Shakespeare, but it’s less not exactly Shakespeare than either of the previous examples. Adding more ability to look at the text that it’s given gives you the ability to produce something that looks more and more like coherent text. You can extend this idea further, letting it look at more characters at a time, and eventually you get something that starts to look almost like coherent English until you try to actually make sense of its meaning.

For context, here’s some output from (someone else’s) toy LLM trained on Shakespeare:

And, do remember, in the ungracious of war.

Hear’s my tent

And see me that crystal’s death, Tranio, he affections of love you.

GLOUCESTER:

YORK:

GLOUCESTER:

In God the curtain are you, this wilful Chertsey monastery a puissant stoop’d me.

GLOUCESTER:

And then, my lord, we were ‘shall’?

KING HENRY VI: widow’d from his foe surprised at once, being so:

As heavy

I am subtle

It still doesn’t make sense, but with each improvement in the complexity of a model its ability to sound almost like it knows what its talking about improves.

One key thing to note in going from the simpler version to the complicated version is that there are now a lot more parameters. Our previous model that just gave every character equal a probability independently of what came before it has 107 parameters - one for each possible character in the text - while our slightly better one that uses the last previous character has 11449 parameters - one for each pair of characters (e.g. the probability of a ‘t’ coming after a ‘c’). This holds in general: The more able to represent language your language model is, the more parameters you should expect it to have. When people are talking about model sizes, they mean the number of paramters. Wikipedia says that GPT-4 probably has about 1.76 trillion parameters.

Getting the structure of your language model right is essential for making sure it can actually represent language well enough to do the job you want it to, but whether it actually does that all comes down to whether the weights have the right value. The third example is only better than the second because of the particular choice of weights! I could just as easily have set it so that the probabilities were all equal and we’d have got something as bad as the first example.

So, once you’ve got the structure of your language model, you need to figure out the right weights to give it. That’s where training comes in.

How to train a language model

So you’ve got a language model and you want to give it a good set of weights. How? Training!

Except, “training” is something of a misleading metaphor. You’re not really taking a language model and teaching it anything, you’re taking a language model and creating a new language model more suited to your needs. “Training” is what we call that though. It’s also called “reinforcement learning”.This technically means something more specific, but don’t worry about it.

We do this by defining what’s called a loss function. This is some program that takes a language model and gives it a score. You want to create a language model with as low a score as possible.e.g. a loss function could be a measure of how many mistakes it makes. The process we use is what’s called gradient descent. This is a very conceptually straightforward processwith a huge amount of technical detail to make work well enough, which basically consists of taking your current weights, and finding a very small adjustment to them that descreases the loss function slightly.How to actually find that is a little bit technical. You can imagine trying lots of small variations and seeing if any of them work, but usually it’s possible to do better than that. Getting this step fast is one of the big things that we’ve needed to develop a lot of robust technology in order to make progress in this field. You replace your weights with those modified ones, and keep going, You do this for as long as you want, stopping when you can’t find any way to improve the loss function or, more likely, you’ve exceeded your budget for computer time. When training a model, you start from some previous model that you got from your last training run, or if you don’t have one you just set all of its weights to arbitrary values (typically random), and then you use gradient descent to improve it.

A large language model is trained in two stages. Funnily, these are called “pre-training” and “post-training”, with no training stage. These correspond to different loss functions.

Pre-training produces what is called a “base model”, which is a language model that is not particularly well suited to being used as a chatbot, but has taken in a large body of text (typically a decent chunk of the internet). Here, the loss function feeds it many short chunks of text, and measures how often it correctly predicts the following text. In this way, the base model ends up “learning” a lot of the knowledge encoded in its text, because it is able to represent it well enough to predict what comes next.It could of course do this by memorisation, and sometimes it will do this, but generally you don’t want it to do that. You want it to encode the knowledge in a way that generalises to unfamiliar text, representing it as efficiently as possible. One of the things that helps you do this is making sure that the text you’re training on is much much larger than the model, which is part of why training is so data hungry. It will sometimes memorise anyway, but this is a bug not a feature.

Once you have a base model, you create a chat model in the post-training phase. This involves creating a loss function that represents “how good it is at being a chatbot”. You do this by giving it a large number of starting texts to a completion engine using the model (some of which might be as simple as “Human:”, letting it generate the whole conversation, and some of which might have quite specific prompts), running the completion on it, and then scoring the result in some way. The average score over all those prompts is your loss function, and post-training is designed to make the model behave well with those prompts.

Some of this loss function is as simple as things like “Does it hand back to the human in a reasonable time?”. Others might evaluate whether it gets correct answers to particular questions (e.g. if you ask it arithmetic questions, does it give you the right answer?). Others yet might be more nebulous things, like “Is it helpful, harmless, and honest?”. That’s where RLHF, reinforcement learning from human feedback, and preference models come in.

Using preference models in training

One of the basic features of training a large language models is the use of human feedback, comparing two or more different completions and rating which one is better, or marking a particular answer as harmful, wrong, etc. You want to be able to incorporate this into your model training. However, this would be intolerably slow. Gradient descent makes many small changes, and asking a human for feedback at each point in that process would take literally forever.

Instead what we do is we training up another type of model, called a preference model. A preference model takes some piece of text and gives it a score, which we expect to correspond to a score that a human would give it This gives us a program that we can use as a good proxy for human feedback: We expect it to score texts roughly as a human would.You may of course be noticing that there’s a key problem with this: A preference model can only learn the texts as well as its structure allows it to. If humans are scoring things well or badly based on whether they’re correct in some way an LLM can’t actually represent, the same will be true for the preference model.

A preference model is constructed in roughly the same way as a language model, with a set of weights that you can train up to minimise some loss function:

- We put together a large number of examples along with the score they “should” have, or pairs where we say which one is better (e.g. a choice when asked which of two LLM answers you prefer). These scores are set up so that a lower score is better, as with a normal loss function.

- We define a loss function which is lower the better the preference model predicts those scores.

- We train a preference model to minimise that loss.

In post-training, we then perform our reinforcement learning to minimise a loss function that comes from the preference model: We run the completions on our training set, score them according to the preference model’s rating of them, and calculate the loss function as some combination (e.g. an average) of those scores.

When the preference model is calculated by predicting humans raters’ responses, this is what’s called RLHF: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback.

A nice thing about this process is that it allows us to “bank” our ratings. We don’t have to keep asking humans the same questions over and over again, or running expensive tests, we can build up a large body of scored text and use that for training the preference model. It also generalises better, because the preference model learns quite general forms of the sorts of features that are preferred.

Another approach you can take is RLAIF, reinforcement learning from AI feedback. This is exactly the same sort of thing, but your raters are now previously trained LLMs who have been given a constitution that says how to rate responses, and these are used to produce your training data for the preference model. This is Anthropic’s constitutional AI approach and despite all the ways it causes your eyebrows to raise when you first hear it, it reportedly works very well.

TBD

There’s probably more to say here and I’ll update this in response to human feedback.